3. Contested Spaces

In 2009, an EDUCAUSE white paper showed the ubiquitous nature of course-management systems with 95 percent of the respondents reporting using some form for distance or hybrid purposes (Arroway et al. 2010). After all, with the electronic distribution of content, along with conducting projects, providing feedback, and assessing work, it is no mystery why course- and learning-management systems are popular among institutions and faculty members. Course management systems, and arguably learning management systems, let the instructor control the content. On the other hand, there are elements in the C/LMS that allow students to scaffold their experiences through creation of wiki modules or participation in discussion board posts; however, the controls the instructor has at her or his disposal are much greater than the panels the students have access to within their interfaces. This control led us to consider how the design of the overall interface of Blackboard, Canvas, and Coursera link to gender and class. Given the history of computer programming as an exclusive boys' club, where middle-class men shaped the technology and left out the women (Abbate 2012; Wajcman 2006), it is no surprise that certain ideological values are present within certain C/LMSs. For example, C/LMSs not only reflect middle-class distinctions through the use of icons associated with white-collar labor practices like business cards and manila file folders, but the platforms also have embedded power differentials that affect how students and teachers interact and react in those spaces. This gendered and classed space, once appropriated into institutional spaces like C/LMS technologies, becomes a norming platform where restrictions upon gender, race, and class mark nonwhite males as other, but also all student-learners who do not identify with the value-laden designs, iconography, and infrastructure the platforms provide. These factors, left unexamined, contribute to an overall ethos suggesting familiar scripts of patriarchal influence and hegemonic practices. While learning-management system providers, like Canvas, suggest they have built the online space with learners in mind, we have found through our analysis that C/LMS spaces reinscribe power dynamics through surveillance practices, constraints upon identity expression, and limited student participatory action.

Cyberfeminist stance on surveillance practices in C/LMSs

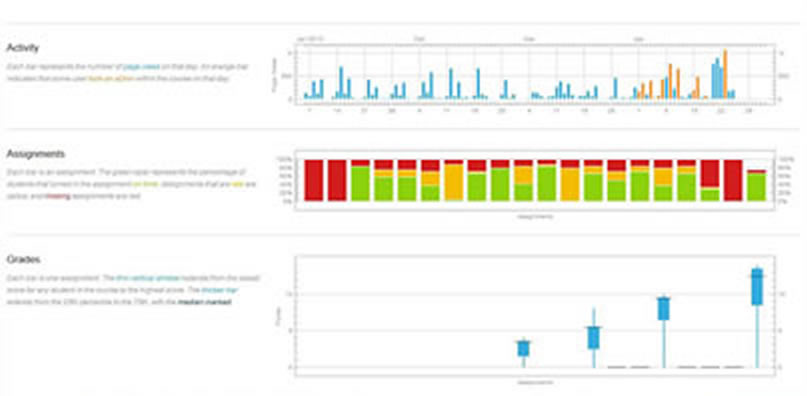

The ability to use surveillance techniques to monitor behaviors suggests an authoritative relationship, and it is present in the C/LMS platforms, especially in Canvas, where teachers have the ability to use surveillance technologies to track students (see figure 1.1). This disturbing trend of providing these features can highlight spatial dominance and marginalization through Michel Foucault’s (1979) notion of panoptic power. Namely, the types of surveillance tools available to teachers within these platforms re-inscribe the types of oppressive workplace conditions that mark workers’ bodies as sites of observation and classification to document behavior.

Figure 1.1. Canvas analytics: The array of collected analytics Canvas offers teachers include page number views over a period of time, percentage of assignments completed by student, and median scores on assignments. The images have been blurred to protect the identity of the students with this illustration.

Kevin D. Haggerty and Richard V. Ericson (2000) argued that Foucault’s metaphor of the panopticon helps draw attention to contemporary surveillance; however, the metaphor has gaps in understanding how human bodies are abstracted from their physical, social, and cultural settings. Thus, Haggerty and Ericson theorized that a “data double” equivalent occurs in online spaces from hundreds of data points about a user. The actions and behaviors that the data points reveal about users are divorced from the social and political contexts that people embody in real life, nor do the data reveal ways people learn and engage with online spaces. We apply this perspective to C/LMSs and the analytics and surveillance practices of those environments. Our concern rests with the potential to other our flesh and blood students if teachers take action based upon the data, as the data do not give a full portrait of the ways students engage, interact, and learn from online learning spaces.

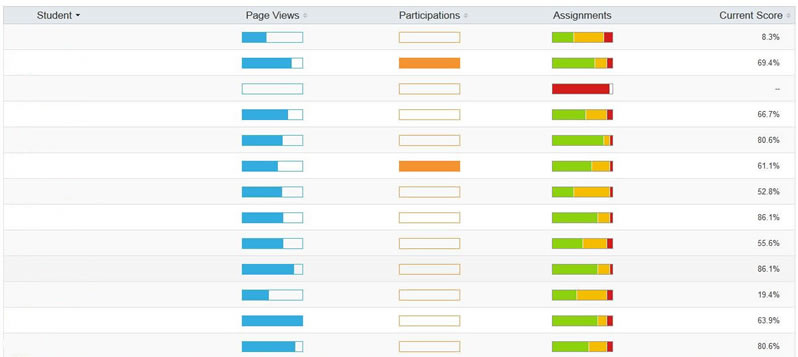

Using surveillance tools to observe online behavior and act upon those interpretations may re-inscribe power differentials that may lead to subjugation instead of empowerment. An illustration about the claim regarding behavioral expectations and the practices that frame them occurs through the “assessment” feature in the control panel within Blackboard (see figure 1.2) and the “view course analytics” selection in Canvas. Both tools allow the course instructor to view the site activity and actions taken by students in both spaces. For example, Blackboard’s assessment feature allows instructors to view when and how long students engaged in the course space. Canvas, on the other hand, allows teachers more information. Not only can instructors see the number of page views per student, but the information is conveniently color-coded as green, orange, and red in Canvas (see figure 1.3). These behavioral practices of surveilling student electronic activity in Blackboard and Canvas, taken further, create a re-inscription of power differentials with the teacher being the “authority” and the students being subordinate to that power.

Figure 1.2. Blackboard control panel: The control panel in Blackboard gives teachers multiple options to add and recycle course content, as well as view performance and statistics of student users enrolled in the course.

Ultimately, our concern with this type of surveillance offered to teachers lies with marking students' “data double” bodies as sites of classifying student participation in ways that perhaps enforce and reinscribe authorial roles in virtual spaces, especially if the course instructor acts upon the data both C/LMSs provide. The potential to silence or marginalize students by acting upon the data may occur because the social and political matrices students bring with them in online spaces are not captured by the algorithms that collect user clicks, downloads, and time spent in a module in the course space. The act of Blackboard and Canvas tracking certain movements online accounts for a fraction of student engagement in C/LMSs and the course material overall. The data from the analytics simply do not consider the full portrait of student engagement in virtual spaces.

Figure 1.3. Teacher view of student participation in Canvas: Canvas tracks, per student, the number of page views, level of participation, completion ratio of assignments, as well as the current grade for each student.

Constraints upon identity expression

Along with the surveillance made possible by C/LMSs, this chapter examines the embedded class and gender markers within the interface, which represent a type of learning space corporatization. In some ways, this corporatization is reminiscent of corporate entities with a top-down managerial approach with white men predominately at the helm, and workers busily performing tasks that aptly describe the ways the C/LMSs under discussion operate. Indeed, there are an array of tools and tracking technologies at the instructor’s disposal, but students are left with truncated access to the platform. Thus, Mary Hocks’s (2009, 251) notion of “Who has the power?” leaves us acknowledging that the power rests with the teacher, and not the students in these course spaces.

The teacher–student relationship within these platforms runs parallel with the managerial style of the white-collar/blue-collar dichotomy we see in corporate workplaces. As Shoshana Zuboff (1988) said of the roles of the bodies in these two spheres, “Blue-collar workers used their bodies in the service of acting-on, to transform materials and utilize equipment. White-collar employees use their bodies, too, but in the service of acting-with, for interpersonal communication and coordination” (98–99). The design of each platform allows the power to flow through the teacher as a body “acting-with” information through the interface to the students who “act-on” that information through task-making of assignments and activities. For example, in the Coursera spaces, the design of the interface, in many cases, is little more than videos of talking heads (see figure 1.4), usually professors sitting in their university offices, providing short informational lectures. They are “acting-with” the information and disseminating it to the thousands of students who in turn “act-on” the lecture by taking multiple-choice quizzes or by participating in discussion board posts. Functioning as a teacherly template, the interfaces vest power with the instructor through the medium of a machine, which transmits material to students who then consume and perform rote-learning tasks. This approach does not leave much for students to work with in terms of expressing material in ways that may make more sense for them.

Figure 1.4. Still images from Coursera instructor videos: Representative examples of videos of instructors providing lectures to students enrolled in various Coursera courses. The images have been blurred to protect the identity of the instructors with this illustration.

Additionally, closely examining the design of C/LMS interfaces reveals the embedded power flows of the corporatization of online learning spaces. As Manual Castells (2000) contended, power has shifted from organizations and institutions to the network, and while networks allow for decentering and defragmentation, the network has embedded the cultural codes and power in itself. As Radhika Gajjala and Yeon Ju Oh (2012) noted, this has become a question for cyberfeminists: “How must we respond to the pleasing discourses of women’s empowerment through blogging, networking, financing, or entrepreneurship when we suspect that digital technologies, intertwined with neoliberal market logic, exercise subtle, indeed invisible, power?” (2).

In examining the design interfaces under discussion in this chapter, the iconography and hierarchal structure reveal the kinds of capitalism and class privilege that Selfe and Selfe (1994) noted. As an example, some of the icons in the Blackboard platform—like the computer screen, paper, and business cards (see figure 1.6)—link to associations with which corporate codes of middle-class white men stereotypically engage. The most egregious example of embedded power is the icon of the business card. Certainly, a business card provides ways for those in the middle to upper classes to hand off a contact card for networking opportunities. Yet the business card implies a certain cultural code and identity marker about a person’s class and standing more so than their personal information. The card can be a status symbol, depending upon the organization the person works for, or can work for, and acknowledges a person’s rank within an institution. To associate an icon of a business card to personal information in a C/LMS platform works to inscribe cultural codes of identity, class, and standing upon the student.

The association promotes an unspoken hegemonic practice of suggesting what types of identity markers are appropriate for and allowed within such a space, while at the same time silencing or ignoring the types of personal information or expression about identity the student may want to express. Erica Kubik (2012) emphasized that “cultural codes of conduct are organized around patterns of identity, which, while possibly inclusive, are also very rigid in definition” (137). Kubik suggested that the corporate cultural code of the business card forms a narrowed conception of identity. Additionally, the lack of student expression may lead to less participatory action on the part of students because the iconography and hierarchy designs may not be understandable to students who aren’t part of or do not engage with those identity markers.

Figure 1.5. Blackboard tools: The icons Blackboard uses in the tool feature include a business card next to personal information.

Limiting student participatory action as seen through MOOCs

While both Blackboard and Canvas are primarily used in conjunction with institutions to provide distance and hybrid learning to their enrolled students, there has been considerable movement in the area of massive open online courses, or MOOCs, since Dave Cormier first coined the term in 2008 during an invited talk with George Siemens and Stephen Downes (Cormier, 2012). Since then, organizations like Coursera, edX, Udacity, and Udemy have split from the early model of a MOOC—now known as a cMOOC—into what has been termed an xMOOC. According to Dave Cormier (2012), the MOOC emerged as a response to having large amounts of information at our disposal through distributed networks; the MOOC isn’t just a course, it’s a way to connect with others and share information. Thus, a MOOC is participatory: its very nature facilitates engagement with the material that the course facilitators provide; ideally, the cMOOC could be fashioned into a cyberfeminist space. In contrast to the cMOOC, the xMOOC (which Coursera and other companies have capitalized upon), moves away from the connectivist roots of MOOC and instead promotes video lectures and quiz taking as methods of learning material. Indeed, as George Simens (2012) noted of cMOOCs versus xMOOCs:

Our MOOC model emphasizes creation, creativity, autonomy, and social networked learning. The Coursera model emphasizes a more traditional learning approach through video presentations and short quizzes and testing. Put another way, cMOOCs focus on knowledge creation and generation whereas xMOOCs focus on knowledge duplication.

Although there is ample discussion board space dedicated to just about any group formation from asking questions, providing more information from outside the course, or even talking about topics unrelated to the course, the Coursera platform operates as an institutional learning management system providing content to thousands of students. In short, the xMOOC is a significant departure from the founding ideas of the cMOOC.

With the variation of the xMOOC, the types of behaviors students must engage in to be successful within the course and its space reflect the types of power differentials and templates of the C/LMS spaces of Blackboard and Canvas. Yet this variation goes one step further by revealing how limiting student participatory action is within the space of an xMOOC, especially with the Coursera platform. Given that the origins of MOOCs valued networked learning with autonomy and creativity, the type of participation needed to achieve those goals suggests that students are culling large amounts of data from the Internet and sharing that information with their peers in an effort to learn more about a subject. Coursera’s platform allows teachers to disseminate content with little connectionist work on the part of the student; thus, the xMOOC spaces continue to reinscribe power differentials that favor the instructor(s) and not the students. The Coursera xMOOC space has become a virtual representation of the traditional model of face-to-face lecture and test, mirroring Freire’s (1970) banking concept of education.

Finding safe spaces

Understanding when C/LMS platforms limit student learning and participation is crucial to conceiving how to usher in alternative online platforms or programs that foster feminist practices of expression, engagement, and sharing, as not only women, but all sexes and genders, interact in an online space. While we admit that any online space has the potential to limit expression and participation, we also see merit in finding spaces that do so in the fewest possible ways. Another characteristic we suggest looking for when choosing an online space for educational purposes is how amenable the space is for identity formation and expression. Ability to alter colors and information display is one thing, but being able to reorganize a space to suite learner needs and desires is another. Finally, we might also reflect upon the theoretical position of the cMOOC—to create open lines of participation and creativity, and to foster engagement and autonomy as we search for and use spaces to share information with each other. With that said, we also acknowledge the pioneering work that the contributors of FemTechNet are doing with their instantiation of a “DOCC”—that is, a distributed online collaborative course that allows institutions, researchers, and students to participate in a collaborative themed course that departs from the xMOOC model by integrating feminist principles in the model (see Juhasz and Balsamo 2012). We look forward to the developing work the DOCC offers our intellectual communities. Finally, by analyzing and reflecting upon course spaces and by moving to more egalitarian spaces, we come closer to lessening some of the constraints we unintentionally place upon students and ourselves.

1. Introduction

2. Our historical quest for safe spaces

3. Contested spaces

4. Taking back the spaces

5. Conclusion

6. References