To understand the affordances and constraints of the proposal to swap computer lab spaces, it is necessary to begin with a snapshot of the institutional contexts. Our campus has some unique features that make it challenging to meet the needs of all students. Our campus is a small branch campus of a research-focused state institution. We are a commuter campus with a population of approximately fifteen hundred students who are approximately 23 percent minority (28 percent of freshmen), and at least 50 percent are first-generation college students. Although the National Center for Educational Statistics indicates that most undergraduate students are between the ages of eighteen to twenty-four, our undergraduate students average age is twenty-six. Despite many students having families and work outside of school, 73 percent of our undergraduate students attend full-time. Approximately 12 percent of our students are military veterans (campus “Facts” 2011). Most of our students are expecting to procure or maintain full-time employment after graduation; only a very small number of students consider going on to graduate programs.

There is also something to be said about the invisible force of an institutional legacy. The fact that our campus began as a training ground for local government-employed engineers—a bit of a specialized vocational beginning—infiltrates and permeates the campus. Students routinely demand practical applications and have little patience for theoretical underpinnings. In a class I taught surveying elements of graphic and document design, for example, a student turned to me in clear frustration and asked why there wasn’t “just a manual to follow” for all of the design principles because she didn’t have time to think about all of the issues. The murmur of other students in the class indicated she wasn’t alone in her frustration. As was the case with the specialized vocational training that started our campus before it became a branch of the university system, many of our students want skills and applications that can immediately translate into job skills.

For these students to become competitive on the job market, they have the greatest need of all for the kind of flexible and collaborative, tech-friendly learning spaces that computer labs can offer (Walls et al., 2009). What complicates issues affecting space allocation for us is the very real and very palpable context that exists in our ever-present growing pains. After becoming a member campus of our state institution in 1989, our campus offered courses only for upper-division undergraduates. It wasn’t until fall 2007 that our campus admitted its first cohort of thirty-five full-time enrollment freshmen. In 2009, that number grew substantially to one hundred. Since then, our unprecedented growth in enrollments, programs, and course offerings has made staying ahead of student and program needs extremely challenging, particularly because new classroom buildings that would include new instructional computer labs are not expected in the next decade. We’re out of space; we lack sufficient space for faculty, staff, and students.

The process of space requests in institutions is a slow process involving many layers and levels of stakeholders, committees, and so forth. It can, and often does, take years to develop and implement large-scale changes in infrastructure and space use. One of the affordances of working at a branch campus is that this process can be somewhat streamlined. Although the time investment remains similar across state institutions, our budget status, independent from the main campus, means that we often can avoid sending space requests beyond our chancellor to the state capital-planning department. This means that I have a clearer sense of my audiences in the proposal process and how to strategically appeal to each of them through the mission, goals, and land-grant mandates of our campus.

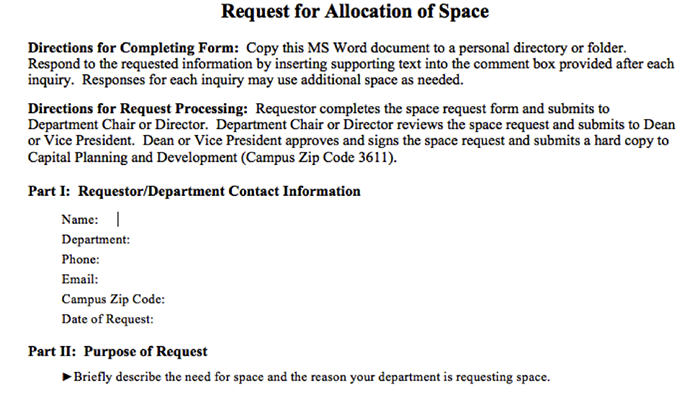

Developing the proposal first involved addressing my area director through the strategic five-year plan I was asked to create for English and the Writing Program for our campus. It also involved meeting with the computing and networking manager to get estimates for equipment and software and to discuss the logistics and time frames possible for new labs, upgrades, or reconfiguration of existing labs. I met with the campus vice chancellor to talk about space availability, long-term planning for buildings and equipment, and possible funding opportunities that could address our computer lab needs. I learned from the vice chancellor about the typical process for university space requests and how woefully inadequate the request form would be for our needs. As seen in figure 8.4, the request form allows very little ability to describe and define the needs or reasons for requesting the space or space changes.

Noting that the form expects a departmental representative to file the request, my first small potent gesture (à la Selfe1) involved making my case for improved computer labs to the area director on campus. I needed to ensure that this person was going to advocate for the need in my stead. I addressed this audience by making the computer labs part of our strategic plan, noting that the labs fail to meet not only the needs for English and for the Writing Program in general, but also for the Digital Technology and Culture program. And when the merger of the College of Liberal Arts with the College of Sciences resulted in a new reporting line for me, I took it as an opportunity to present the proposal to a new audience.

1. Drawing on the work of Henry Giroux and Michel de Certeau, Cynthia L. Selfe (1999) initially put this phrase into circulation to discuss the ideological underpinnings revealed in the small, consistent, every-day activities that can reify marginalization and colonization. As she explained in her article with Richard J. Selfe (1994), such processes occur “not in a totalizing fashion but through many subtly potent gestures enacted continuously and naturalized as parts of technological systems” (486). As I use the phrase here, I refer to the kinds of everyday activities that can help along proposals, such as the hallway discussions that serve to remind administrators of pending decisions or pressing needs.