4.4 Collaboration

Collaboration is an integral component of our program, for both students and postdoctoral fellows—instilling a sense of community and a sense of teamwork as normal and productive for social and professional relationships. While we explicitly help students learn to be better collaborators (for example, learning about performing various roles, avoiding groupthink, and managing conflict), we also have created spaces that make collaboration easier. Two space challenges involve balancing the need for collaborative work with the need for privacy and recognizing that virtual collaboration is as common as face-to-face collaboration.

How does space affect collaboration for students?

The first experience of collaboration is a sensory one. One sees, hears, and feels it happening and is by virtue of the experience pulled into being a collaborator, whether one intends to take part or not. In the front of the Communication Center, beanbag chairs line the walls, easily seen from outside the glass walls of our entryway. Many students enter the center simply to ask about the beanbag chairs and whether the area could be used for general study. (The answer is “No.”) These chairs act as a hook—through the window of our center, students see a casual and welcoming space with a cool design and a relaxed atmosphere. They might come to check out the chairs, but they stay for the tutoring.

However, the purpose of the beanbags is twofold: while they do hook the students into coming inside the Center, they were designed to promote brainstorming. Set up around one of our movable whiteboards, the beanbag chairs provide students with a flexible atmosphere for brainstorming. Dawn Johnson (2002) explained the evolving definition of the word brainstorm: “The very origin of the word 'brainstorm' suggests disorder. It dates from the late 19th century as 'a severe mental disturbance' and in the 20th century has come into corporate jargon as a conferencing term” (p. 11).

The collaborative process of brainstorming is messy and uncertain, so we wanted the space to reflect mental freedom. The beanbag chairs can be moved around, and large whiteboards offer colorful and easily erasable options for jotting ideas. The space helps students both become more at ease with the disorder of the process as well as embrace the process, coming to understand its benefits as a tutor guides them. The whiteboards offer more freedom than the written page, as Johnson (2002) discovered in her work with brainstorming students: “There’s a tyranny in the printed page that keeps student writers from questioning what they’ve written. They feel trapped into the formulations they’ve set down on paper; they can’t think of new words because they’re looking at the old ones” (p. 12). The whiteboards, on the other hand, emphasize transience and invite erasure; because multiple people can work on the whiteboards at the same time, tutors can also jump in to draw lines, make notes, or erase unhelpful bits of thought that may be tyrannizing the student. See Figure 14 for the planned informality of the beanbag brainstorming area in the Communication Center. See Figure 15 for brainstorming revisions based on a usability testing session at one of the “egg” tables in the Hall Building.

Figure 14: Students lounging on the beanbag chairs in the Communication Center, brainstorming on one of the many whiteboards.

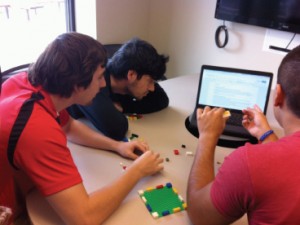

Figure 15. Student group at one of the “egg” tables in the Hall Building. They’re working on a project in Dr. Olga Menagarishvili’s technical communication class, revising a set of instructions based on usability tests they conducted. Photo credit: R.E. Burnett © 2013. Used with permission.

How does space affect collaboration for professionals?

One way to support faculty is to provide spaces for collaborative conversations. Physical spaces for informal conversation and collaboration are built into the work areas of the postdoctoral fellows in the Hall Building, near the kitchen area, on the terrace, and in the public areas (see Figure 16).

Spaces for more formal collaboration are also designed into the Hall Building. The postdoctoral fellows have themselves formed writing groups that meet regularly to review and critique each other’s work (see Figure 17).

Figure 16. (L to R) In the one of the Brittain Fellow conversation areas in Hall 105, Dr. Mollie Barnes and Dr. Leah Haught discuss how to build wikis. Photo credit: R.E. Burnett © 2013. Used with permission.

Figure 17: Brittain Fellows Writing Group that meets bi-weekly. (L to R) Dr. Aaron Kashtan, Dr. Jonathan Kotchian, Dr. Joy Bracewell, Dr. Rachel Dean-Ruzicka, and Dr. Christine Hoffmann discuss a draft of one of the Writing Group members at an “egg” table in the Hall Building. Photo credit: R.E. Burnett © 2013. Used with permission.