Introduction

In the previous chapter, we outlined the benefits of paying attention to writing workflows, to seeing how writers break down the tasks involved with writing and fit them to specific tools, enact them in specific practices, and link them together over specific histories and situated events. We argued that the field can develop more complete pictures of writing processes and people's investment in them or frustrations with them when they are viewed as workflows. More than that, when writers explicitly consider their tasks from a workflow perspective, they invite creative and serendipitous approaches to assembling and reassembling their writing tasks, tools, attitudes, and environments.

This chapter argues that a sociocultural perspective on writing lays the foundation for defining and tracing writing workflows by widening our perspective past the moment of inscription and broadening the roles that tools play in writing. Drawing especially on the work of Paul Prior and Christina Haas, we describe how sociocultural approaches emphasize how people, tools, discourses, and practices develop together over time in ways that disrupt conventional accounts of agency, motivation, and cognition. Without such a perspective, "writing workflows" could be reduced to simple choices of one tool's features over another or varying procedures that could each result in similar products or texts in the end. While choosing tools and tinkering with practices are aspects of workflows that we will focus on throughout this book, these aspects are inextricably linked with affective orientations, motivations, rich histories of tool development culturally and tool appropriation by individuals, and the complex mediation of consciousness and action distributed among a wide network of actors. As our case studies show, choosing one tool over another is not such a simple act, however much it might seem inconsequential or random to observers or even to writers themselves. Instead, these choices are the nexus of intersecting lines of histories, and they reverberate through the present to mediate writers' use of these technologies and the practices in which they are embedded.

Calls for More Research on Writing Processes

As described in the previous chapter, we position the theoretical lens of the writing workflow as an extension of writing process research, one that attends more closely to the mediating tools involved in literate activity. Through this extension, we see this book as responding to recent calls other scholars have made to return to empirical research into writing processes. These scholars have narrated histories of the value of early process research and declining interest in such work in the field (Shipka 2011; Takayoshi 2015; Van Ittersum & Ching 2013). Each points to the turn in the 1990s toward exploring the social contexts of literacy as the reason for interest in process research drying up.

Jody Shipka has described two historical phases of research into writing processes, from the cognitive approaches of the 1970s and early 1980s exemplified by Flower and Hayes, to a "social view of process" that "tried to attend more closely to the situated, social, and interpersonal dimensions of the individuals' and groups' production practices" (32–34). This latter approach has since been criticized as "perhaps a bit too situated" (34) in its "readers, writers, and texts as independent objects" (Syverson 1999; qtd. in Shipka, 34–35).

Pamela Takayoshi (2015) traces declining interest in process research to the social turn, arguing that

since the social turn took hold in rhetoric and composition (indeed, took hold across disciplines), researchers expanded their lenses from looking at writing as a process, labor, or practice to look more broadly at literacy as it functions in social contexts. (3)

Similarly, Van Ittersum and Ching claim that in the 1990s, "scholars became less interested in what was happening in the heads of writers and more interested in the social contexts within which they wrote" (n.p.). This expansion in focus, Takayoshi argues, has led to less interest in "empirical, data-based" methods in favor of "theoretical scholarship" (3–4). All four of these scholars point to a return to empirical methods as a means to rekindle inquiry into writing processes. Takayoshi, in particular, directs scholars' attention to the digital tools and environments involved in writing:

Writing spaces are dramatically different than they were 25 years ago, and the field of Writing Studies has not yet in any sustained way paid close systematic attention to how this difference impacts processes and products of writing. (4)

We suggest in this chapter that attending to workflows provides the writer a means of encouraging the systematic attention called for by Takayoshi by directing attention specifically to the interplay between the tools, material conditions, and the activities afforded by them. However, we are wary of limiting the word "workflow" to simply meaning a focus on computer software. We see research into workflows as providing the means to examine contemporary writing processes without limiting that inquiry to activity in the head or to the contexts alone. In the next section, we describe how our concept of workflow is shaped by the sociocultural approach developed by Paul Prior and others, with special attention to Prior and Shipka's (2003) concept of "environment-selecting and -structuring practices."

Tracing Literate Activity with Sociocultural Theory

In describing various approaches to studying writing processes, Paul Prior emphasizes the many moments that happen outside of "the immediate acts of putting words on paper" (2004, 167), such as conversation with a friend days before, review of other related texts, the development of the tools and discourses the writer will use, or an observation and the resulting feelings that become the motive for composing the text. Why privilege that particular moment that words are being inscribed when so many other moments have shaped that one so completely? Seen from this perspective, even a quick writing task becomes difficult to fully trace, as it involves discourses, genres, and writing tools spanning years as well as the writer's many lived experiences that shape their engagement in the writing task. Due to this complexity, Prior argues that writing "is not a tenable unit of analysis" but only a "starting point" from which to "trace the literate activity associated with it" (2008, 13). Literate activity, as Prior defines it, involves "reading, talking, observing, acting, making, thinking, and feeling as well as transcribing words on paper" (1998, xi). Instead of aiming to produce complete accounts of writing processes through artificially bracketing off specific moments or scenes of writing, researchers drawing from sociocultural theory have sought to develop more richly detailed accounts of literate activity by widening the scope of what matters.

Sociocultural theory is most often associated with the work of Lev Vygotsky, a Russian psychologist working in the early 1900s. Prior and Stephen Witte each offer accounts of Vygotsky's "understanding [of] human consciousness as sociohistorically produced" (Prior 2006, 55), that it "develops historically through the individual's engagements, via tools, in practical activity and through the individual's interactions with others via language and other signs" (Witte 2005, 131). This focus on tools and their role in the development of consciousness makes sociocultural theory especially attractive and useful for our investigation of writing technologies and their role in writers' processes. Prior provides a distilled overview of the approach:

Given Vygotsky’s (1987) emphasis on the genesis of tools (material and psychological) and people (learning/development) and Voloshinov’s insistence that language (indeed any type of cultural sign) is "a purely historical phenomenon" (1973, 83), sociocultural approaches emphasize concrete chains of history and the complex ways temporality is folded into people, objects, environments, and practices. (2015, 187)

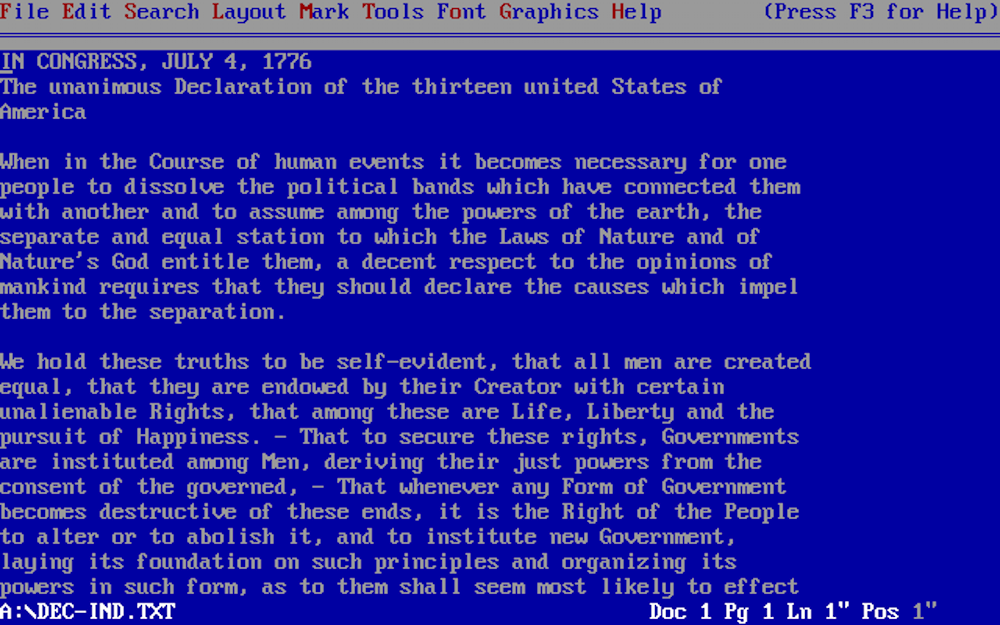

In other words, in this book, we trace the development of tools and people over time to understand how they came to be tied together in a particular workflow at a particular moment in time. This means, for example, understanding how the history of word processor development and adoption throughout the 1980s and 1990s led to certain versions of Word and our participants' antipathy toward the interfaces and feature sets of that software. It means understanding our participants' varied writing tasks, how they learned to complete them, and the various combinations of writing tools they've used over time in similar or different contexts. It means tracing how the physical places where they write shapes their tool selection and vice versa. It means accounting for the ways older word processor interfaces (predating graphical user interfaces) are folded into the stark interfaces of the text editors our participants prefer and the role of nostalgia and aesthetics on those preferences.

While all writers make use of many tools (including the language they write in, the concepts they write about, the writing instrument and medium, etc.), the writers in this study intentionally seek out new software and hardware tools to use, meaning that tracing all the connections between tool development and learning would be a much longer, and frankly more boring, affair. Instead of tracing everything, in this book we focus on concrete writing activities, as Prior suggests: "to move beyond chanting such lists of mediational means [tools] as a kind of sociohistoric mantra, we need to weave tools into specific accounts of writing, to give these silent tools a voice in the constitution of activity" (1998, 180).

One key aspect of the sociohistorical approach to tools is the focus on two kinds of development. Christina Haas (1996) describes these as "technology in process," meaning the "process of use and process of development." Studies that examine both kinds "entail examining not only the transformative power of tools on consciousness, but also how the tools themselves get made, and how they get transformed" (18). First, we can trace any individual's use of a given tool over time. For example, one of our participants initially started using the text editor TextMate but was unimpressed by its minimal interface, thinking this implied lack of affordances. Over time he began to use its more advanced features, even building additional functionality into the application through writing and distributing plug-ins. Second, we can trace TextMate's development itself. This could mean starting with the development of computer text editors and how they are different from word processors. It would involve tracing the development of TextMate itself, which stalled in 2007, leading many users (including the participant in our study) to use other applications. Beyond looking at single tools involved in an activity, Prior suggests several scholars have extended Vygotsky's approach by also examining the "sociogenesis of functional systems" (1998, 188). A functional system is both "typified and fleeting" and "tie[s] together people, artifacts, practices, institutions, communities, and ecologies around some array of current objectives, conscious or not" (Prior et al. 2007, 19).

One of the benefits of the "historical-genetic" approach, Haas argues, is that it becomes "difficult to continue to posit computers, or any technology, as amorphous, omnipotent agents of change, suggesting instead that a given technology's effects may be varied, elaborate, complicated, and far from immediate" (18). None of the writing technologies described in this study (or elsewhere) can be seen as providing singular answers to writing challenges. While our participants may frame some applications as "the answer" to certain challenges they may have faced, we see these as always partial answers that often bring their own challenges and are time-limited in their usefulness as the whole ecology of tools and tasks changes over time.

A particular challenge for scholars working from sociohistoric theory is maintaining a perspective on literate activity that keeps in mind the situated concrete actions of a writer (one who is, say, working with a particular text editor to compose a legal brief) as well as the dispersed histories that play a role in that activity (previous mindmapping and writing activity that led to a written plan for this brief, the previous times the writer has written legal briefs, previous uses of the text editor, previous writing activity in general, experiences with the client, etc.). Prior and Shipka (2003) demonstrate one approach through their research interviewing academic writers about how they have engaged in a specific writing project. They direct their participants to draw two pictures: the first depicting what the writing activity looks like (including places, resources, people, and feelings involved) and the second to "represent the whole writing process . . . from start to finish" (182). Prior and Shipka then followed up on the drawings in the interviews.

Through these "thick description[s] of literate activity" (185), Prior and Shipka offer accounts that stitch together the situated actions with the chains of historical moments that have shaped them, typically through a focus on the mediating role of tools and other objects. They describe a writer who does the laundry while revising articles so that the regular breaks to pull clothes from the dryer and fold them provide a time and space for mind-wandering. They show a writer who uses a card table to block their writing space as a "punishment" so that finishing the writing project results in the "reward" of being able to move freely in the space. They recount the many conversations one writer had with a friend at a bar that provided help in "managing affect and motivation" (197) while working on a dissertation prospectus. Rather than depicting literate activity as some kind of unique cognitive process or set of tools, Prior and Shipka argue:

Literate activity is about nothing less than ways of being in the world, forms of life. It is about histories (multiple, complexly interanimating trajectories and domains of activity), about the (re)formation of persons and social worlds, about affect and emotion, will and attention. It is about representational practices, complex, multifarious chains of transformations in and across representational states and media (cf. Hutchins, 1995). It is especially about the ways we not only come to inhabit made-worlds, but constantly make our worlds—the ways we select from, (re) structure, fiddle with, and transform the material and social worlds we inhabit. (181–82)

We seek to depict and trace literate activity in this way, through a focus on workflows. In our case studies of writers, we ask them to recount their histories with writing and computing, and we trace the histories of technologies through various means. Beyond this well-established sociohistoric approach, we follow Prior and Shipka in their attention to the ways writers engage in "environment-selecting and -structuring practices (ESSP’s), the intentional deployment of external aids and actors to shape, stabilize, and direct consciousness in service of the task at hand" (219).

Prior and Shipka's naming of ESSPs provides a crucial theoretical structure for this book. While this section began with the identification of Vygotsky's central insight as the fact that consciousness is not a stable entity but instead is produced historically through engagement with tools and activity, such an insight can be difficult to understand concretely. One might accept that a computer affords a different composing experience than a pencil, but ultimately one might feel as if their consciousness is not profoundly different as a result of using one or the other to write. This feeling, we would suggest, is more the result of common understandings of writing activity as predominantly the transcription of mental thoughts rather than close examination of what writers do and why. Examining why and how writers choose and create specific types of writing environments unearths many fascinating accounts of writers' motivations, emotions, and levels of concentration. Sometimes writers struggle to put into words why they prefer to work in certain ways, ultimately landing on some variation of "This way feels right" or "This is just the way I do it." Accounts by some writers of their writing practices have for decades depicted the ceremonial nature of their routines for "inviting the muse" or just working productively: working regularly at a particular time of day, using particular paper and pens, listening to certain music or requiring absolute silence, and so on. We might translate here the everyday phrase "getting into the right frame of mind" as pointing to the practices that actively "shape, stabilize, and direct consciousness in service of the task at hand" (Prior & Shipka 2003, 219).

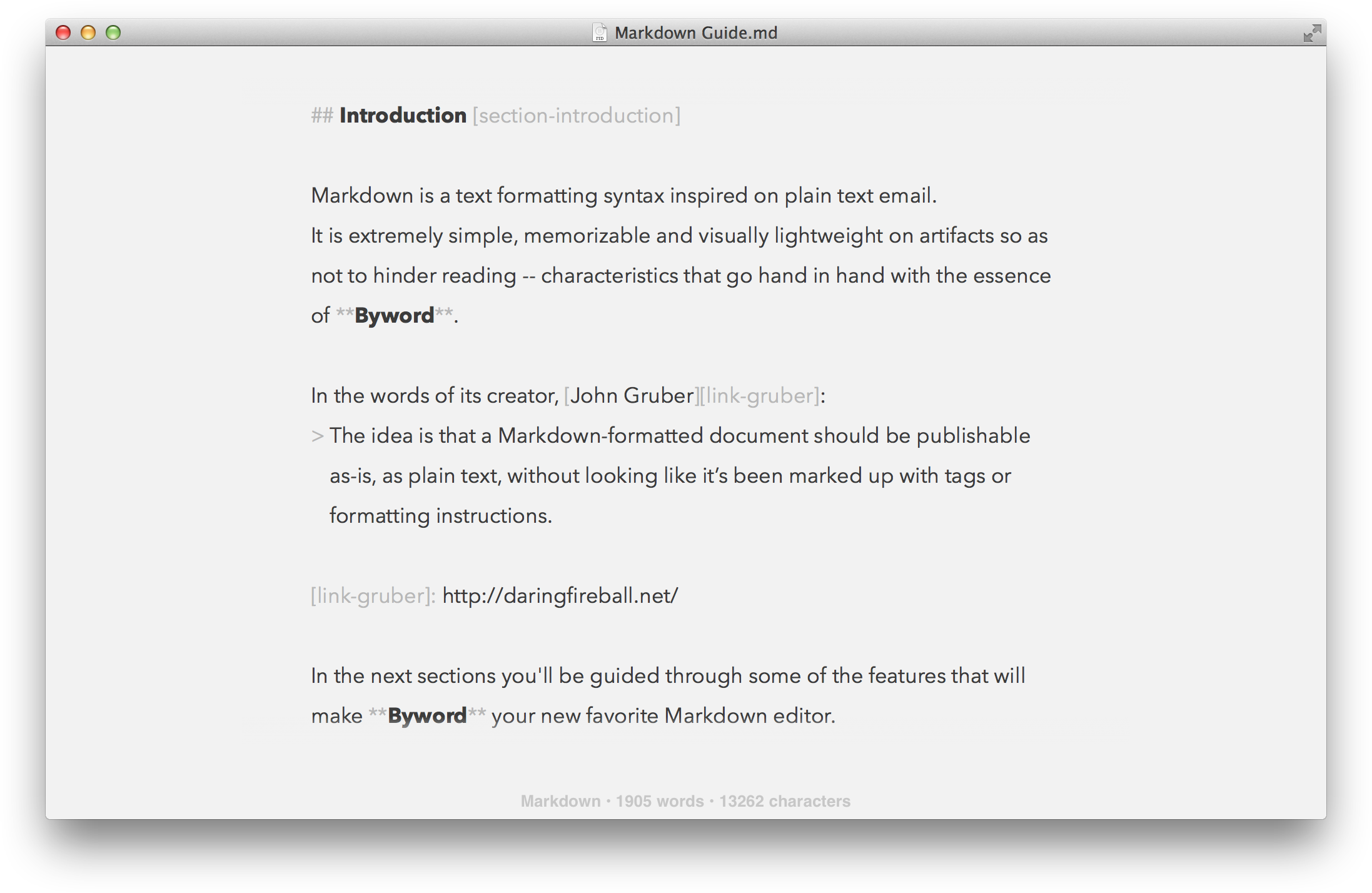

In this book, our case studies focus on literate activity, on writing and computing practices rather than centering on specific technologies. While the technologies our participants use are interesting, provide valuable affordances uncommon in conventional word processors, and should be better understood by scholars in Writing Studies, they are not uniquely special in their abilities to help writers write in particular ways. As Christina Haas (1996) reminds us, "A practice account of literacy acknowledges these material tools and technologies; [but] also posit[s] technology as only one of a complex of factors that impinge on thinking and doing in context" (19). We began with curiosity about the tools and what they afforded (Markdown in particular), but we quickly realized that the more interesting story was the approach to technologically mediated writing activity these writers took.

In drawing on Prior and Shipka's concept of ESSPs, we follow Van Ittersum and Ching (2013) in extending our inquiry beyond physical practices and into the realm of software. We lose a good deal of the picture when we ignore the various ways people choose sparse or cluttered interfaces, arrange their windows just so, or design additional software tools to prevent the need to switch away from a writing application to a web browser. Selecting and structuring interfaces plays a large role in our participants' work, as we detail in the subsequent case study chapters.

Participants

Before we began this project, we were both readers of blogs and listeners of podcasts that generally focused on Apple products, writing, and productivity. It was this interest that led Tim to introduce himself to Derek after hearing Derek's brief appearance on a Mac Power Users episode devoted to interviewing listeners, talking about how he uses software for academic writing. This personal interest became a scholarly curiosity when we both began focusing on Markdown, a writing technology and a common denominator between the many blogs and podcasts we were following.1 Derek initially wrote about Markdown bloggers as a community of practice, describing their relationship to distraction-free writing applications (many of which use Markdown to format plain text documents) (Van Ittersum & Ching, 2013). From here, we initially began planning a research project devoted to studying writers who compose in Markdown.

We began the project by identifying two writers who were prominently associated with Markdown, hoping that they could make introductions to two more writers and lead us to other participants in a snowball sample. While we were able to recruit two more participants to be interviewed, it was a challenge to recruit more. The first two writers we interviewed were David Sparks and Brett Terpstra, who provide two of the case studies in this book. As we analyzed their interviews and compared them to the other two, we saw more reflection and detailed description on their writing practices and their interests and motives for using certain technologies. We attributed their increased fluency in this area to their efforts to provide writing instruction, in the form of blog posts about using Markdown, self-published guides to using Markdown, creation of writing tools, and so on. In other words, Sparks and Terpstra served as links between our field and these technology enthusiasts. While they aren't involved in the discipline of Writing Studies, they are interested in writing as a process that one can teach and learn. As we became more interested in focusing the study on these writers, we also identified Federico Viticci as another writer who writes in Markdown and offers writing instruction, in the form of a self-published manual on using the iPad writing application Editorial, as well as more informally in blog posts, email newsletters, and podcasts. We did schedule interviews with Viticci a few times and he signed our consent form, but, unfortunately, we were not able to connect with him to conduct an interview. However, we see his role as an innovator on the relatively new platform of iOS as an important perspective to include in the book. We have found several blog posts and podcast episodes where he addresses most of the topics we would have asked him about, although of course he does not directly answer the questions we would have asked (and did ask Sparks and Terpstra).

These three writers (Sparks, Terpstra, Viticci) are interconnected professionally in many ways and are part of a larger affinity space (Gee 2004; 2005) focused on enthusiasm for Apple products and productivity. Viticci and Terpstra have both appeared on Sparks's podcast Mac Power Users many times (four and six times, respectively, at the time of this writing), Terpstra is listed as a contributor at Viticci's MacStories, and Terpstra and Sparks have cowritten two books of tips for Mac users. While they all have different perspectives on writing and different tasks involved in their professional lives, their professional connections and co-participation in this affinity space more broadly means they often draw on and contribute to common resources and practices as they develop and work with their personal workflows.

As we began to identify and trace what it means to engage in workflow thinking and to devote time and energy to specifically creating, improving, and experimenting with workflows through our analysis of these writers' activities, we found their connections and shared context an important advantage for the study. We could trace how different participants engaged with the same applications and how they put them to use in different ways. We could see how reviews or comments from one participant shaped another's use.

Most important, we could see that a shared interest in workflows provided an exigence for these writers to document their workflows and thus offered more reasons to reflect carefully on their writing practices and tools. On the one hand, we do not hold up these three participants as exemplars, as role models for writing students or scholars. They have an enthusiasm for technologies that shapes their interest in tinkering with new applications and devices at a more frequent pace than other writers might need or want. Yet on the other hand, these three enthusiasts are documenting and teaching writing practices—activity that is at the core of our field, where we should be the enthusiasts. In the affinity space where these writers participate, a common practice is documenting and experimenting with workflows, and for these three that often means writing workflows. We see this style of engagement as a useful model to emulate more explicitly in our field. To be sure, such work takes place in different forms in conference presentations, workshops, classrooms, and even scholarship. Rather than calling for some radical break with the past, we argue that reworking some key concepts from the field could open spaces for discussion and sharing of practices that too often are taken for granted, individually and socially (see Horner 2015). We will return to this argument in more detail in the final chapter of the book.

Computation, Representation, and Inclusion

The benefits of studying these three connected participants, however, are tied to a significant limitation: All three of our participants are white males, as are we. Within the affinity space they participate in, there are very few nonwhite people, and few women are visible as podcast hosts and bloggers. This is likely linked to the affinity space's proximity to the fields of programming and computer science, which, as Annette Vee (2017) notes:

As a profession, programming has resisted a more general trend of increased participation rates of women evidenced in previously male-dominated fields such as law and medicine. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that only 23.0% of computer programmers in 2013 were women. The numbers of Hispanic and black technical employees at major tech companies such as Google, Microsoft, Twitter, and Facebook are very low, and even lower than the potential employee pool would suggest. High-profile sexism exhibited at tech conferences and fast-paced start-ups now appears to be compounding the problem. (17)

Although we don’t have data about the audience demographics for the workflow affinity group, we can see how the group hovers near the traditional domains of programming and computer science. Conversations often involve programming or scripting solutions, and they tend to privilege concepts such as abstraction, systems approaches, and modular thinking that are taught within the domains of computer science. Within the affinity space, this extends beyond the podcasts, books, and blogs we’ve highlighted in our research. Many of the software applications that our participants use and celebrate are developed by white men, or have employees that fall into gendered categories of work. For example, Ulysses, a writing application that is popular within the affinity group and mentioned throughout this book, lists fourteen employees on its "Team" webpage: seven men and seven women. All of the women work in either marketing or customer service. The seven men, in comparison, are software developers and graphic designers. This labor composition seems typical of the computing industry in the 2010s.

Of course, as both Janet Abbate (2012) and Marie Hicks (2017) remind us, this wasn’t always the case; women once drove most of the major work in computing. And within the field of computers and writing, women were at the forefront of all important work: starting journals, publishing research, and writing software. Many of these women had to push against institutional norms and beliefs that computers weren’t for writers or humanists but were instead the purview of scientists or engineers—fields in which men were the dominant population. Women persevered, bringing computers to writing labs and classrooms, and they built a field grounded in inclusive approaches to computing and literacy.

We—Derek and Tim—have benefited from the guidance and generosity of female mentors, and throughout our work on this project we have discussed at great length the limitation of a participant group consisting of three white men. When we began this study by focusing on Markdown, we accepted this limitation because we could not find any other people who were as vocal and clear about why and how they wrote with Markdown. In the course of analyzing the data, however, we shifted from a clear focus on Markdown, to the workflows that Markdown affords, and finally to simply "workflow" as a concept. We have decided to remain with the data that led us to these arguments rather than searching out new participants for a study of workflows more generally, but we think further studies into the workflows of more diverse writers in different settings are important and certainly called for.

We are also dedicated to inclusive work and pedagogies, and we hope this book offers a practical contribution that can be broadly adopted across many learner populations and perspectives. We don’t want to speak only to young white men who are interested in the nerdy facets of writing technologies. Instead, we want to work toward an inclusive approach to technologies through which all writers feel comfortable and can find community in the creative use of and experimentation with their writing tools.

Finally, as we talk about the limitations of our participant group, it’s important to note that our participants are personally committed to similar goals. We have been reading, listening to, and generally following their work for years, and we have found them to be compassionate and generous people who have supported important equitable causes. All three, for example, have used their publishing platforms to advocate and fund-raise for App Camp for Girls. Although we remain mindful of and transparent about the demographic limitations of this study, we think it represents a broader cultural problem and not something tied to our participants or their particular affinity space.

Study Design

This study began with our interest in Markdown and exploring the motives writers had for using it. We left Markdown out of our research questions to keep them broad so that we could frame participants' Markdown use within larger motives or practices that they might share with us. Our study, then, focused on these two questions:

- How can writers evaluate the increasing numbers of hardware and software writing tools and processes now available?

- What role do technical skills play in writing activity?

Following our approval by the Institutional Review Board in late 2014, we began interviewing participants via Skype and recording their interviews with their permission. Our interview protocol followed a semi-structured approach (Charmaz 2006; Selfe & Hawisher 2012; Selfe & Hawisher 2013; Spinuzzi 2013). There were eleven standard questions that we asked of everyone, but we allowed each interview to go in different directions depending on how participants answered the questions, or what activities each participant engaged in (e.g., we spent more time talking about software development with Terpstra and more time talking about writing processes with Sparks). Although we were focused on Markdown in these interviews, we used the term "workflow" in our questions because this was the word that our participants used to describe their writing practices and tools. In using this term, we were looking for how Markdown fit with the various writing tools and practices they used.

For the chapters focused on David Sparks and Brett Terpstra, the interviews form the main data set for our analysis. We also reviewed blog posts and podcast episodes as a check on our interpretations, making sure these additional sources fit the patterns we saw in the interviews. For the chapter focused on Federico Viticci, we scheduled an interview on two separate occasions over the course of a year but were not able to connect. We then formed a data set from every blog post and podcast episode where he discusses his writing workflow.

After transcribing the interviews, we imported the transcribed data into an Excel spreadsheet, following Cheryl Geisler (2003). We independently analyzed the data segmented by turns by first using an open coding scheme (Corbin & Strauss 2008; Saldaña 2013) with constant comparison to identify initial patterns. After discussing the codes each of us had used, we identified "friction" as a key concept related to how and why these participants adopt new tools and practices. We worked to develop a clear definition of this term and then independently coded again. After this coding round, we discussed segments in the transcripts that we did not both code as "friction" until we reached agreement. Rather than employing an outside independent rater, we followed Peter Smagorinsky (2008) to “reach agreement on each code through collaborative discussion rather than independent corroboration” (401). In working to understand friction and its role in these writers' adoption of new or different tools, we transitioned from focusing on Markdown and the writing processes it affords to thinking about "workflow" as a concept of its own.

After identifying "workflow" as the key idea in our data that we wanted to understand, we examined how descriptions of friction from our participants led to workflow design or refinement. We then sought to trace those workflows over time by going back to the participant's blog posts and podcast episodes, looking for further explanation or description of particular workflows and the workflow thinking they exhibited in making them, checking that what they described in the interview was consistent across other data.

We thought carefully about how to represent the workflows within each case. Although the flowchart is a common means of representing workflows in industry and professional contexts, we deliberately avoided that kind of representation in our case chapters. Instead, we wanted to emphasize each participants' workflow thinking as the focus of each chapter rather than packaging their workflow itself as a model for readers to learn and adopt (although we provide enough links to each participant's publications that interested readers can follow these to learn the workflows). Additionally, we thought that depicting their workflows as diagrams would erase some of the rich context of friction that our participants were working against, especially because that friction provides the context from which their workflow thinking emerges.

We do find visual depictions of workflows to be valuable in other ways, as we describe in more detail in our discussion of workflow mapping in chapter 6. When writers themselves produce palimpsestic maps that depict the historical changes to their writing workflows over time, their maps are intimately tied to embodied experiences engaging in that writing activity, and they offer a reflective richness than isn't seen in prescriptive flowcharts. Approached as a reflective practice, we see great potential in workflow mapping, and we hope that it, along with workflow thinking, will help others push this project in new and different directions.

Case Study

Our interest in the workflows of these participants led us to a case study approach in a trajectory described by Anne Haas Dyson and Celia Genishi (2005). They describe how researchers start from their interest in the "local particulars of some abstract social phenomenon" (2–3):

The aim of such [case] studies is not to establish relationships between variables (as in experimental studies) but, rather, to see what some phenomenon means as it is socially enacted within a particular case. (10)

In this study, we set out to understand what writing with Markdown means to the writers we interviewed. We presumed that our participants were not going to be exemplars for the field of Writing Studies, that this study was not about proving how some new writing technology led to better results than the word processors common in our field. We agree with Christina Haas's (1996) conclusions drawn from her analysis of Vygotsky's work: "The effects of technological change (e.g., computerization) on writing are profound, but certainly not unitary, easily predicted, immediate, or consistent across contexts" (16). Rather than conducting experiments or tests with our participants, students, or others related to Markdown, we sought to develop a detailed picture of how Markdown fit within our participants' lives. As our analysis has progressed, we have shifted to exploring how writers establish their workflows and how they make them meaningful.

While we are not seeking to generalize from our participants' workflows in order to prescribe workflows that writers in the field of Writing Studies (scholars or students) might use, we do see some value in determining what aspects of conceptualizing writing activity as a workflow might be valuable for writers in our field. We don't think Markdown is likely appropriate for many student writers, but thinking as carefully about one's tools as the participants in these case studies may be warranted. In other words, we are looking to generalize from these cases in particular ways, similarly to Annemarie Mol's (2008) discussion of a "trajectory":

Good case studies inspire theory, shape ideas and shift conceptions. They do not lead to conclusions that are universally valid, but neither do they claim to do so. Instead, the lessons learned are quite specific. . . . It does not apply everywhere. This is not to say that its relevance is local. A case study is of wider interest as [it] becomes a part of a trajectory. It offers points of contrast, comparison or reference for other sites and situations. It does not tell us what to expect—or do—anywhere else, but it does suggest pertinent questions. Case studies increase our sensitivity. It is the very specificity of a meticulously studied case that allows us to unravel what remains the same and what changes from one situation to the next. (9)

Following Mol, we aim to use these case studies of workflows to contrast with the discussions of writing tools and writing processes in Writing Studies. The trajectory we embark on from these studies is to find ways for scholars, teachers, and writers in the field of Writing Studies to more explicitly invent writing workflows and to approach their writing activity with "workflow thinking."