x

Contents

Home

Home

Home

Some Context

Shipka

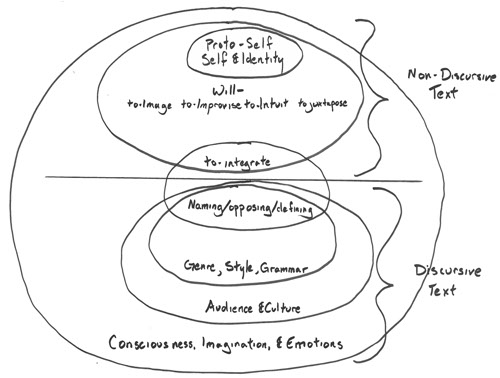

Drawing of figure 4.2, Murray 151.

Although this book is working between a number of fields, it finds its home in rhetoric and composition and serves as a response to a few different conversations there. Four books in particular led me to compose arguments about multimodal scholarship multimodally: Jody Shipka’s Toward a Composition Made Whole, Susan Delagrange’s Technologies of Wonder: Rhetorical Practice in a Digital World, Patricia Sullivan’s Experimental Writing in Composition: Aesthetics and Pedagogy, and Joddy Murray’s Non-discursive Rhetoric: Image and Affect in Multimodal Composition. Each of these books sheds light on multimodal composition from a different angle. But these books are not enough, so I will indicate a lacuna, a noticeable gap in the field.

Shipka’s 2011 book serves as an answer to Kathleen Blake Yancey’s 2004 call for a composition made whole. Yancey reminds us that the move toward new media in composition does not mean a move away from the written word. Digital and print overlap. They depend on each other and remediate each other. Thus, Yancey calls us to make composition whole, to strive for coherence across media and modes. Shipka points out that despite Yancey’s examples being digital, this call reaches to the nondigital as well. Shipka refuses to abandon the nondigital in the face of new media and articulates a call for multimodal composition that continually brings in newer (and older) media. This is not to say that Shipka ignores multimodal composition. Rather, she dives deeper into the history of multimodal composition than most scholars. While many are content to see multimodal composition as a new phenomenon, Shipka exposes its secret history, with motivations and questions lurking in Quintilian and a robust literature arising in the 1970s and 80s coming out of calls for more expressive writing.

Shipka worries that the influx of digital media in composition will marginalize alternative multimodal work (8-11). She returns again and again to a pair of ballet shoes on which a student (literally) wrote a

research-based essay. The shoes cause her colleagues outside of composition to hem and haw, wondering if this is really writing. Shipka’s choice of artifact is compelling. The shoes resist generic classification and upset their readers’ expectations before the reader has even read a word. When we teach our students about media we teach them that, in some ways, the medium will always be the message. Choosing a medium is a rhetorical decision, and one Shipka advises her students to make carefully. To write on shoes is to already say something surprising, or at least in a surprising way. What should we make, then, of Shipka’s own rhetorical decisions?

One of the most interesting moments in Shipka’s book is the final one. Having argued persuasively for a composition made whole, Shipka reflects on the uncomfortable irony of using linear text to talk about multimodality:

I too am cognizant that some could find ironic or problematic the way I have decided to present the argument and illustrations offered in Toward a Composition Made Whole. One may wonder why—especially in light of many of the texts that are described and illustrated throughout the pages of this text—I have produced a fairly traditional looking print-based, linear, argumentative text. (149)

It certainly might seem ironic to not just discuss but argue for multimodal student composition without composing one’s own arguments multimodally. Writing about multimodality seems a bit like “dancing about architecture,” as the old saw* has it, but using one medium to describe another is hardly the cardinal sin of academia; in fact it is at the core of art history. Later we will investigate this particular history and the incommensurability of image and text. For now, I will agree with Shipka in finding it somewhat ironic, while also pointing out that it works well within our professional bounds. Perhaps these professional bounds need to be investigated more closely. Academia demands texts about film, art, dance, and so on but discourages films about film, dances about dancing, art about art, or comics about comics. Of course, each of these postcritical moves is happening now, as we will soon see.

Rather than questioning these professional bounds, Shipka can be read as strengthening them. She closes the book by responding,

The approach to communicative practice outlined here does not advocate creating texts or facilitating change that simply results in the substitution of one set of sign systems, technologies, and limitations for another or that privileges certain ways of knowing, learning, and composing while denigrating or downplaying the value of others. Rather, a composition made whole is concerned with attending to the ways in which individuals work with, as well as against, the meditational means they employ in the hopes that this, in turn, will help empower individuals to choose wisely, critically, and purposefully the relationships, structures, and representational systems that are most fitting or appropriate given the purposes, potentials, and contexts of one’s work. In choosing to re-present my work in the way I have, I have attempted to choose wisely, purposefully, and appropriately. (149)

While Shipka has spent the previous 150 pages enumerating multimodal composition’s merits, the implication that it merely substitutes a new sign system for the old one could undercut her case. I disagree with this implication on two fronts. First, multimodal composition does not work as a sign system in the same way that print does. I will explain this more carefully as we look at Joddy Murray’s parallel arguments concerning nondiscursive rhetoric. Second, to advocate or employ a new mode (I will resist using sign system here) does not necessarily denigrate another mode. Difference does not always imply hierarchy. Shipka admirably defends her own choice of medium with the same criteria she teaches her students: choose wisely, purposefully, and appropriately. I wholly agree with Shipka on these criteria, as I think any rhetorician would. Media are not good or bad, there is no hierarchy, but they can be seen as appropriate or inappropriate to a particular context. As always, kairos must guide our rhetorical decisions.

We might then ask how kairos guides Shipka’s choice of medium here. Looking at her book as a response to particular rhetorical situations, we can identify an exigence within our discipline: nondigital texts are being neglected in current theories of multimodal composition. There is, of course, another academic audience with different constraints that points us to a very different exigence: tenure. However, tenure does not seem to be the primary constraint on Shipka’s choice of medium: “my department (and university) would have been open and is, in fact, increasingly open to alt forms of representation” (Shipka, “RE: Toward”). Instead, based on our correspondence, Shipka articulated the constraints that guided her decision as far more complex: worrying that a multimodal argument either would not get read or would be read but marginalized due to its form, preferring the tangibility of a print book to share with loved ones, and worries that her argument would be misunderstood as marginalizing print. Each of these constraints operates on the assumption of a conflict between multimodal and print-based arguments, whether multimodal arguments are marginalized by academia or the public or whether multimodal arguments inherently marginalize print-based argument. There seems to be an assumption in academic and public audiences that multimodal and print-based scholarship cannot coexist. Shipka does not necessarily assume that this conflict is true or valuable but believes that it is assumed by her various audiences. I would argue that we need to question that assumption more directly if we hope to see change across academic and public audiences. For composition to be made whole we need not just print-based or digital scholarship but the kind of

nondigital multimodal work Shipka analyzes and extols.

Although Shipka leaves this question somewhat open in the final sentence of the book, she has indeed attempted to choose wisely, purposefully, and appropriately. However, the last of these criteria, appropriateness, is in constant flux. We measure the appropriateness of an academic argument by how well it meets the expectations of the rhetorical ecology in which it finds itself. Its audiences are not static, and the audiences Shipka addressed in 2011 have already begun to change. The question Shipka opens at the end of her book is answered implicitly by Susan Delagrange by composing multimodally about multimodal composition.

While Susan Delagrange is hardly the first to compose her scholarly arguments multimodally (she provides a fantastic review of previous endeavors), her 2011 Technologies of Wonder is one of the most visible and influential digital monographs yet. That the book was awarded both the Computers and Composition Distinguished Book Award and the Winifred Bryan Horner Outstanding Book Award further displays the book’s influence and prowess.

Delagrange created a complex hybrid project, at once unprintable book (too expensive due to its many luscious color images) and unsurfable webtext (the final text is a pdf, perhaps best read on a tablet). But Delagrange always intended this in-betweenness: “I began with the premise that form and content cannot be separated, and that the visual, structural, and interactive design of my project would always already be an inextricable part of its meaning” (xi). The many images do not operate only as examples but serve to create their own arguments that work alongside the arguments Delagrange makes in the text. Her argument that form and content cannot be separated is not unique. That assumption resides behind most new media scholarship in rhetoric and composition. As Cheryl Ball and Ryan Moeller point out, this false dichotomy concerns not just new media but writing as well. In each, form and content are imbricated just as much as in any other medium (3).

Delagrange argues that we need to cultivate a sense of wonder in our students and in our own writing about and with visual/digital modes and artifacts. She centers this argument on a revitalization of the rhetorical canon of arrangement. Delagrange foregrounds arrangement* across the form and content of her project. She discusses the surprising and often disruptive power of arrangement in student, popular, and academic writing, while bolstering that argument with surprising, powerful, wonderously disruptive arrangement in her own project. For Delagrange, arrangement is not just a contingent requirement of the final project; arrangement is a mode of inquiry (176).

Comics fit Delagrange's model well. Her juxtaposition of image and text, the hybridity of the artifacts she examines and of her argument, and the feminist desire to include the excluded each apply to my own argument about comics. I argue that reconceptualizing comics through the interplay of figure and discourse powerfully broadens comics’ scope while focusing its function in productive ways. As hybrid artifacts, comics ask readers and creators to oscillate back and forth between various modes. I follow Delagrange by composing arguments in comics’ modes and challenge others to likewise employ those and other modes in ways that I will no doubt find surprising.

Finally, Delagrange’s feminist lens calls for us to ask, “Who is diminished, devalued, or (more insidiously) left out?” (176). While we should certainly bring the exiles into the mainstream, I think there are equally valid reasons to also try to follow the exiles out. As Claire Colebrook writes,

One should not just affirm “woman” as the other, as different and beyond the strictures of patriarchy; one should, following Irigaray, look at the way oppositions between identity and difference have been defined on the model of the male subject. Only then can becoming-woman be affirmed as more than the celebration of what is different from man. Only then can difference be thought not as a value within a field of already defined terms but as what goes beyond the image of man as a thinking being who recognizes, defines and orders difference—what Deleuze refers to as the “image of thought” (Difference and Repetition). (“Introduction” 4-5)

The marginalization of comics calls for serious academic work, not just to bring them in but also to

bask in their minority. As Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari argue, minor literatures deterritorialize language, connect individuals to political exigences, and demand collective assemblages of enunciation (Kafka 18). I discuss comics' deterritorialization of language when I look at the various binaries across which they operate. Their demand for collective assemblages of enunciation is met, in a sense, in the very form of my own figural discourse. All this to say that I do not in any way disagree with Delagrange’s feminist lens (I teach it, employ it, cherish it, and defend it). However, I would argue against any who would want to infer that Delagrange insists that everything left out must be brought in. It is just as important to also create lines of flight out.

Delagrange’s book fits within a larger movement of alternative scholarship in rhetoric and composition. Patricia Sullivan’s Experimental Writing in Composition: Aesthetics and Pedagogies glances off that movement. Sullivan’s real goal is to critique current theories of teaching (not producing) experimental writing: What are the various schools? What purpose(s) does experimental writing serve? What has changed or needs to change?

Sullivan outlines two pedagogical approaches to experimental writing: expressivist and political. The former assumes an autonomous subject who strives for authenticity. The latter rejects the autonomous subject, arguing that political forces hem us all in, leading these theorists to create “multicultural, social constructionist, or postmodern pedagogies” (45). These two positions overlap to a larger degree than my summary indicates, but they also each entail their own problems. Expressivist experimental writing can alienate students from each other: an expressive, autonomous subject has no need for others, let alone collective action. Likewise, political experimental writing threatens to strip the other’s discourse of its the otherness: when we bring comics or punk into the classroom, we sanitize them and make them just more academic discourse.*

Regardless of the pedagogical path one takes to experimental writing, the teacher will be hard-pressed to form rigid evaluative guidelines for assignments that experiment, whose very goal it is to break out of academic prose. Sullivan reviews a variety of approaches and settles on reflective essays as the most productive (or perhaps, least useless) way to evaluate experimental writing. Still, the reflective essay does not solve the problem. The reflective essay asks students to assert their intentions, once again assuming their autonomy, and to contextualize their experiment into the classroom, reappropriating the nonacademic into the academic. Joddy Murray has expressed similar criticisms of the reflective essay as assessment tool.

What stands out, though, is that the issues with experimental assessment distract us from the issues inherent in any assessment. Assessing experimental writing is so noticeably impoverished only because we pretend we can assess traditional writing. But we assess traditional writing just as poorly as experimental. We assess only those features that we really don’t care about: mechanics, structure, how much it looks like the platonic ideal of an essay in my head. Most of us want student essays to be essays, that is, attempts or experiments. We always assess experimental writing, regardless of medium. Unfortunately, most of our assessment tools discourage experimentation. Likewise, Sullivan similarly argues that all student writing is experimental. No technology or aesthetic will save us from the questions that have always haunted composition. In the course of her critique, Sullivan mentions a few avant-garde compositionists: Wendy Bishop, Jeff Rice, Geoff Sirc, Greg Ulmer, and Victor Vitanza, among others. However, she focuses not on their avant-garde styles but on their avant-garde claims. Although arguing that content and form cannot be separated, Sullivan consistently ignores the styles (form) of her interlocutors’ arguments (content).

Sullivan’s work is an excellent and much needed critique that pulls together a wide swath of scholarship. However, we still need macro arguments about alternative or experimental scholarship. We need someone* to outline the current alt-academic scholarship that is being and has been done, tracing those roots backwards as far as we might go.

This project is not that argument, but I hope it will take part in it. Rather than overviewing all of the alternative scholarship that is currently going on, I will attempt to theorize my own alternative scholarship, explaining why it is so important that scholars take part in it, that they do not allow themselves to become alienated from their own rhetoric.

In Non-discursive Rhetoric: Image and Affect in Multimodal Composition Joddy Murray articulates a model of multimodal composition close to my own. Leaning on research within philosophy and neuroscience, he argues that thinking is made up of images and that emotion is not a physical or mental phenomenon—it is both. Each of these arguments problematizes composition as it is currently taught. The assertion that image precedes discourse leads Murray to question composition’s privileging of discourse. The assertion that emotion infuses itself into reason leads him to question any privileging of cold, rational prose.

At first glance, neither of these takeaways seems all that radical. The expressivist movement pushed back against emotionless prose decades ago. More recently, the field of multimodal composition has called for more image making. Murray separates himself from other scholars with his clearly articulated values of multimodality and his innovative

Nondiscursive-Discursive composing model. Murray ends the book by proposing a set of five values of multimodality: image, unity, layering, juxtaposition, and perspective. Murray’s composition model is made up of a nondiscursive half that precedes and makes possible the discursive half. Within the nondiscursive half, he proposes a variety of wills: Will-to-Image, Will-to-Intuit, Will-to-Improvise, and Will-to-Juxtapose. A final will, the Will-to-Integrate, builds a bridge toward the discursive half of composition. Taken together, a conscious, willing, writing subject appears. But this appearance is a kind of fiction generated by a variety of recursive processes. It’s here that Murray occupies a space between process and postprocess, or perhaps outside that continuum.

As Murray has argued, we composition scholars tend to unwittingly privilege discourse. Murray doesn’t notice that he privileges discourse by thinking of image as a kind of language. Throughout Murray’s nuanced account of nondiscursive symbolization, he makes no mention of the place of nonsymbolic rhetoric. Following Diane Davis and Thomas Rickert, I argue that some rhetoric is nonsymbolic, but also that nonsymbolic rhetoric provides the foundation for symbolic rhetoric. Rhetoric is prior to symbolization. Suffice to say at this point that I disagree with Murray, but that disagreement is primarily terminological. Of course, terms matter. From a Burkean perspective, they construct the screen through which I perceive. To adequately account for our differences would entail an in-depth analysis of each of our terministic screens. I will in subsequent sections attempt to explain both our terminological differences and what I see as the consequences of those differences.

Despite its growing interest in multimodal rhetorics, the field of rhetoric and composition still needs to build a compelling rhetoric of multimodality. Shipka, Sullivan, Delagrange, and Murray have begun that process. However, there is still much to do. The relationship between image and text is still largely being conceptualized from the point of view of text. This isn’t surprising. We’re trained to read text.

I think comics can offer us a way of thinking through this relationship more rigorously. Comics’ interplay of image and text puts them at the center of conversations about new media. New media also rely on interplays of image and text, though none so explicitly and obviously as comics do. I will begin to move to comics and then beyond comics to other media.

As we go forward, I will explicate my conceptualization of comics as the juxtaposition of image and text and then complicate that conceptualization by rejecting the image/text binary in favor of Lyotard’s terms discourse, figure.

So far we have concerned ourselves mainly with the discipline of rhetoric and composition. From here we will move out into three other disciplines: comics, art, and philosophy. Each of these has something interesting to say to rhetoric.

Before heading on to that, though, let's stop for a quick overview of the main arguments I will make going forward.

Basque

*Possibly attributable to Martin Mull, though it also seems to have originated twenty-five years before his birth: http://quoteinvestigator.com/2010/11/08/writing-about-music/.

*Why not arrangement?

Delagrange focuses on arrangement, but I have very good reasons to focus instead on delivery. If form and content are really imbricated, then we might start anywhere. Delivery focuses on the materiality of rhetoric, and this materiality is a key concern for us today. Throughout this project, I have been led by George Kennedy’s strange definition of rhetoric as a kind of energy. Within this definition, he counter-intuitively claims that delivery is prior to all the other canons of rhetoric (12). So it is to delivery that I primarily look.

*The question is do we start out together or separate?

*Graduate students, take note!

Shipka

Delagrange

Sullivan

Murray

Screen capture of page 32 from Delagrange.

Delagrange

Sullivan

Murray

Smooth and Striated Spaces ❱

Difference ❱

At this point you may also want to stop and look at two of the asides you may have missed: smooth and striated spaces and difference. They outline some of the key concepts from Deleuze and Guattari with which we will operate going forward.