x

Contents

Home

Home

Home

The System

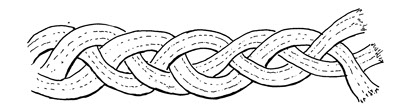

Thierry Groensteen's The System of Comics, an important work that has only recently begun to influence American comic theory, differs vastly from most American work. First off, it is far more systematic than the average American comics studies book. Groensteen erects a structure applicable to all comics and exemplified by the best of comics. His structure breaks down along two poles: the spatio-topical system and arthrology, on which more in a moment. He also employs the strategic use of two terms throughout to build this structure: decoupage and tressage. Decoupage, translated as "breakdown," gets used fairly loosely throughout the work, signifying the way a page/work is broken down into discrete units, the piecing together of those units, the indissolubility of the page/work itself, as well as the basic breaking down of movement inherent in sequentiality (Groensteen calls this last meaning “restricted arthrology”).

Tressage, translated as "braiding," signifies something similar: both the generation of meaning through the layering of discrete units and the division of meaning into discrete planes/threads/layers. Both terms come closer to my own decentering of comics than to the sequential definition. The spatio-topical system characterizes the layout of the page and the conversation between various elements. Here Groensteen develops various comics terms and specific definitions of each (such as panel, frame, balloon, image, icon, gutter, etc.) and introduces new terms such as the hyperframe. The hyperframe is the page itself, in which all the units coexist. This subtle move allows him to talk about any print medium that could conceivably be considered a comic (for it must, in the end, exist on a page); however, it also signifies nothing particular to comics.*

Groensteen breaks arthrology into two parts: special and general. Special arthrology refers to the sequence itself, the strip. The sequential definition of comics occupies no more than forty pages of The System. The majority of the book is devoted instead to the definitions of the spatio-topical system, which then provide the building blocks for the final chapter, on general arthrology. General arthrology is the multilayered meaning of a text (comic) erected through the oscillation between tressage and decoupage, or rather, through the tressage of decoupage and vice versa.

General arthrology creates connections across a given page, not just between adjacent panels. It can even be extended to the relationships between elements on nonadjacent pages, which Groensteen calls “tele-arthrology”:

Braiding thus manifests into consciousness the notion that the panels of a comic constitute a network, and even a system. To the syntagmatic logic of the sequence, it imposes another logic, the associative. Through the bias of a tele-arthrology, images that the breakdown holds at a distance, physically and contextually independent, are suddenly revealed as communicating closely, in debt to one another. (158; italics in original)

A more familiar example may help here. Alison Bechdel’s comic memoir Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, is one of the most popular comics to teach at the college level. Many of my readers will no doubt have read or even taught it.

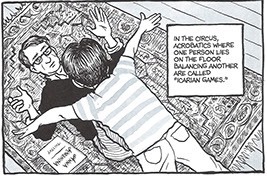

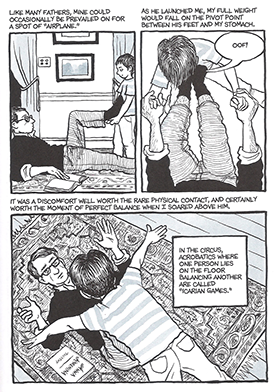

The first page includes a remarkable level of complexity. A young Alison and her father play a game of airplane in which he propels her into the air on his feet. A textbox informs us that such acrobatics are called “Icarian Games,” alerting us to a series of references that will occur throughout the book: Icarus, Daedalus, Joyce. Beside her father lies the book he has just been reading: Anna Karenina. Its well-known opening line alerts the reader that the coming story will be of a family “unhappy in its own way.” Throughout the page we see restrained arthrology in the movement across adjacent panels and general arthrology in the ties between nonadjacent panels (between the first and third panel in which we connect the book) and outside the book to an entire ecology of myth and literature (Icarus, Joyce, Tolstoy).

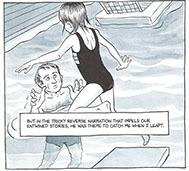

The final page of the comic is similarly complex, though it contains only two sentences. Bechdel has just wondered, “What if Icarus hadn’t hurtled into the sea? What if he’d inherited his father’s inventive bend? What might he have wrought?” (231). The final page answers, “He did hurtle into the sea, of course,” plastered across the grill of the truck that killed her father. It’s a jarring ending, and I have difficulty writing about it without emotion. But Bechdel offers one more panel for reprieve. On top of a panel depicting her leaping from a diving board into her father’s waiting arms, we read, “But in the tricky reverse narration that impels our entwined stories, he was there to catch me when I leapt.” Of course, he wasn’t there. He died, in a sense, just when she needed him most. But through their shared love of books, he lived on to comfort and guide her, and still does. Across time, she still jumps and he still catches. They play across the pages of books.

What’s most striking, though, is the parallelism between the two pages. On the first page, Allison is perched on her father’s feet, about to fall. On the last page he is about to catch her. The framing of the panels stresses the connection. It also imitates the connection she had with her father, one based on intertextuality and common sexual frustrations and explorations. This is tele-arthrology, reaching from the first page of the book to the last, revealing the text as network. It also indicates that intertextuality is a kind of tele-arthrology.

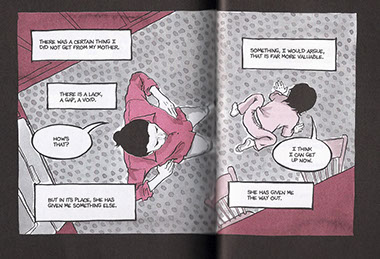

Indeed, in the final pages of her follow-up memoir, Are You My Mother? A Comic Drama, Bechdel creates another parallel to these two panels. Bechdel’s mother is largely absent from Fun Home, but Bechdel wrote Fun Home largely through conversations with her. Are You My Mother? presents that story, with all the difficulties inherent in talking with a parent about the pain and trauma of childhood. On the final pages, Bechdel recounts a game she played with her mother in which she would pretend to be crippled and her mother would help her get around. The final page presents her mother’s failings with brutal honesty. But it also argues for the importance of being taught to help oneself, even if it is by being given some help along the way.

And of course, it is in communication with those panels from Fun Home. Instead of a father holding her aloft precariously or ready to catch her as she falls, we see a mother offering a modicum of care, a “good enough” mother, to borrow Winnicott’s phrase (as Joyce was to Fun Home, Winnicott is the central literary character of Are You My Mother?). But the visual parallels are there. Indeed, it almost looks as though her mother is about to become the airplane Alison will support on one page and on the next it looks as though her mother has dropped her. Rather than being supported in play, Alison is depicted as wounded and in need of care. And her mother offers just enough. Though their relationship seems cold and distant at times, we’ve discovered that it is full of love and shared wounds.

Whether called the gutter or arthrology, the same principle that connects one panel to another or text with image can make connections across books and people.

It should be clear that Rhizcomics employs such tele-arthrology in its hypertextual connections between pages. My goal here is to create an academic comic. However, I’m also arguing that comics aren’t just sequential art or image and text. Groensteen’s terms clarify the other ways that Rhizcomics acts as a comic. Sometimes it is in the relationship between image and text, sometimes in the sequence of panels, and sometimes in the network of connections within and without the book. It should also be clear that these operations are not what separate comics from other media, but what connect them. They’re what comics do really well, and what other media have learned to do as well.

Tressage

Arthrology

Image of page 3 of Fun Home. Click to enlarge.

Image of page 232 of Fun Home. Click to enlarge.

Details from pages 3 and 232 of Fun Home.

Image of page 287 of Are You My Mother? Click to enlarge.

Image of page 288-89 of Are You My Mother? Click to enlarge.

*Groensteen covers over this latter point through silence, but I actually find it quite valuable. It follows that any productive definition of comics will inevitably not only apply to other media, but through reflection, will show that the moves that typify comics are central to all media. That Groensteen passes over this in relative silence makes it all the more important to stress.

Any productive definition of comics will inevitably apply not only to other media but—through reflection—reveal that the moves that typify comics are central to all media.

return to Image|Text

or skip ahead to learn more about Groensteen's decoupage and tressage.