x

Contents

Home

Home

Home

Trans|figuration

At its core, Lyotard’s figure is rhetoric. However, this is not the rhetoric of Aristotle’s appeals, pseudo-Cicero’s canons, or even Bitzer’s situation. Or rather, it is not just that rhetoric. It is also Jenny Edbauer-Rice’s rhetorical ecologies, Thomas Rickert’s ambient rhetoric, and Kathleen Blake Yancey’s new key. The figural—like George Kennedy’s hooting rhetoric—is energy: a drive to speak.

Kennedy investigates animal behavior to find the origins of rhetoric, surprisingly discovering rhetoric preexists not just speech but humans. In one of my favorite examples, he mentions beavers repurposing beaver traps into parts of their dams. He calls this bricolage, noting, “It is somewhat analogous to catachresis in rhetoric, the use of a metaphor when there is no proper word available” (19). The shocking thing about this quote is that propriety seems to have no proper place in it! Why would the beaver be concerned about what the trap was intended for? Catachresis comes into play only if there is a right way (and therefore a wrong way) to use a word. But this assumption is based in discourse, not figure. In other words, the beaver is acting improperly only from our point of view.

Perhaps, then, catachresis is the wrong word. Or, if we’re worried about words like “wrong” in this context, perhaps there is a better word, a more useful word: metalepsis.

Metalepsis does not mean using language figuratively in the wrong way. It means using language figuratively in a new way.

We imagine a pure language, a correct language, which we all learn as children. Our students ask us if their grammar is “right.” But this is to presume that language is like engineering as opposed to bricolage, to use Claude Levi-Strauss’s famous distinction. The engineer uses a screwdriver for one purpose: driving screws. The bricoleur knows that a screwdriver can also be handy in prying open doors, holding down loose papers, and even, if worn hanging from your belt, alerting others to your handiness. As Derrida writes in Writing and Difference, “every discourse is bricoleur . . . the engineer is a myth” (285).

Nor is this relationship one of pure opposition: the engineer is a myth created by especially creative bricoleurs. The screwdriver was created by a bricoleur, not an engineer, who was “mis-using” his implements for something new.

And this is why I have hesitated to embrace Lyotard’s use of the word transgressive. If transgressive means improper, then figural is transgressive only from the point of view of discourse. However, transgressive only means this figuratively. The word itself only refers to “stepping over” something. Stepping over need not be wrong. In fact, it is in this pair that we see how the plane of immanence (to use Deleuze’s terms) can create transcendent categories by folding, transgressing itself. Catachrestic rhetoric is transgressive. Metaleptic rhetoric is transcendent. Rhetoric is trans(gressive/scendent)* figuration.

As with other media, comics tend toward this kind of metaleptic rhetoric. However, unlike most media, comics' constant obvious interplay of discourse and figure contribute to their experimental tendencies in surprising ways. A recent example makes this clear.

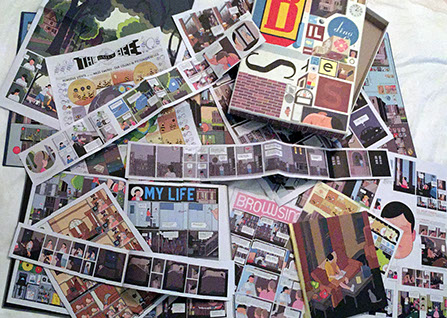

Chris Ware’s 2012 Building Stories could be called a comic book only in the most superficial sense. It is full of the elements we typically identify with comics: drawings, word balloons, panels, strips, emminata, and so on. However, these elements occur throughout a number of artifacts: hardcover books, pamphlets, newspaper foldouts, posters, and even a board game. These artifacts are gathered in a box that includes its copyright information on the inside of the top. Perhaps it would be more appropriate to call it a comic box than a comic book. Either way, based on the decentering of comics I present elsewhere, Building Stories acts more like a comic than most comic books do.

Aaron Kashtan’s recent “‘And It Had Everything in It’: Building Stories, Comics, and the Book of the Future” provides a counterintuitive reading of Building Stories. Kashtan argues that although Building Stories presents itself as a Kindle-proof monument to print books, it depends heavily upon digital technology in both its material construction and its internal logics.

According to Kashtan, Building Stories “portrays chirographic and print media as facilitators of identity, idiosyncrasy, and selfhood” (432). And yet he also notes that Ware seems hopeful for the future of the book, at least of books like Building Stories that reflect their own materiality and ask us to reflect on our own embodiment.

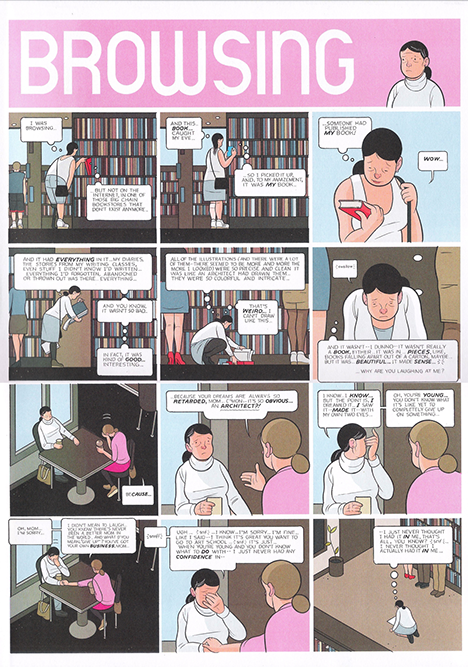

In a crucial section Ware’s unnamed protagonist relates a dream to her adult daughter. In the dream, the protagonist is browsing in “one of those big chain bookstores that don’t exist anymore” and discovers her own book, a book written and drawn in snippets throughout her life. Before her daughter interrupts her, she almost perfectly describes Building Stories itself: “It wasn’t really a book, either . . . it was in . . . pieces. Like, books falling apart out of a carton, maybe . . . But it was . . . beautiful . . . It made sense . . .” (italics and ellipses in original). This also beautifully describes the human experience as described by psychoanalysts, a split subject trying to construct identity out of parts that don’t fit—building stories out of her life. That such a discovery is made in a dream would be even more interesting for Lyotard. When the protagonist’s insight is reflected back on the comic itself, Kashtan reveals that books can do things that e-books can’t and that those things are done most clearly by comics.

Comics revolve around the interplay of not just image and text but discourse and figure. As Groensteen notes, “Comics is not only an art of fragments, of scattering, of distribution; it is also an art of conjunction, of repetition, of linking together” (System 22). Readers create meaning (build stories) out of the disparate elements, whether image and text, panel and panel, or even book and book, as in Building Stories. When confronted with disparate elements, the force of the figural begs us to construct discourse, to “make sense” of the parts. This process is always asymptotic; we never arrive at meaning. Each interpretive step is marked by hesitation. Ware’s box catalyzes oscillation between interpretive leaps and uncertainty, asking us to piece together stories across its various elements. We can never “make sense” of it, but we can make a lot out of it.

I have tried to construct something similar in Rhizcomics. While many assume hypertext to be nonlinear, the hypertext links actually create a fairly linear path. Each is a connection between disparate elements, prompting interpretive strategies similar to those in Building Stories. Readers can then create their own new threads by navigating using the contents, reading thread, or search bar, all found in the top panel. It was important for me that every page be accessible from every other page with a single click: that way readers can create their own threads. Even so, such a process isn’t quite nonlinear. Instead it’s multilinear, approaching the infinite (it would be difficult to number the possible combinations that could be created by clicking through the book, especially when repetition becomes involved).

Figure, felt rhetorically, drives the structure of discourse into movement. Desire would clearly be complicit with figure in that figuration allows it to get what discourse forbids (e.g., Freudian slips). However, this opposition is too simple, too obvious. Lyotard has gone to great lengths to apply Deleuze’s concept of difference to this pair, eschewing mere opposition. If Discourse, Figure is a deconstruction, it cannot simply tell us that figure is good and discourse is bad. It must show us that the opposition itself is impossible:

As we pursue the analysis we come up against a density, an opacity: the locus, I will assume, of the figural that deconstructs not only discourse but the figure, inasmuch as the figure is a recognizable image or a regular form. And underneath the figural: difference. Not just the trace, not just presence-absence, period, indifferently discourse or figure, but the primary process, the principle of disorder, the incitement to jouissance. Not some kind of interval separating two terms that belong to the same order, but an utter disruption of the equilibrium between order and non-order. (328)

And here Lyotard’s supposedly simple misreading of Derrida that I introduced early comes into focus. Lyotard purposefully employs Derrida’s terminology, not to show us that he was wrong but to clarify an ambiguity and correct the misreading with which we began: “the given is not a text” (3). But he also exceeds Derrida’s deconstruction from Of Grammatology, moving toward différance, or perhaps even—metaleptically—offering a new version of différance.

Strangely, this deconstruction has led has to a kind of order. Lyotard carries his analysis deeper into Freud, discovering the oscillating fort/da of the child at play:

What does not come under language, strictly speaking, in the child’s fort/da game, is that it is not in any sense a predication: a basic sentence structure on the lines of a nominal syntagm plus a predicative syntagm. Quite to the contrary, it is the reiteration of two alternating predications that are mutually exclusive:

Nominal Syntagm + Predicative Syntagm

spool (mother) fort

spool (mother) da

It is not the same that returns, neither is it a discourse that unfurls. It is a configuration that does not succeed in liberating itself sufficiently to form a predicative identity in a sentence or in an assertive statement. The death drive sustains this oscillation. Under the guise of a simple linguistic opposition (fort/da), difference, like a void separating the two moments of presence, obtains. The child certainly plays difference, trying to match up the terribly unequal edges of the wound left by the mother’s disappearance. (354)

Figure operates through transgression (but is not definable as transgression). It works with desire. Desire opposes discourse and uses figure to get what it wants. But the reverse is also true. Whence the death drive.

We saw this play out in Building Stories. The figural reappears even in our attempts to create order. Reading Building Stories feels very much like playing a game or solving a puzzle. Each time we try to make sense of it we discover another supplement that refuses to be brought into order. Ware has created a brilliant interplay of order and transgression, allowing the figural a great deal of play.

Order tries to bring transgression itself under control: “Form, even if it is the form of transgression, is not transgression, but the recuperation of transgression within a consistent whole. It is a function of identity and unity” (Lyotard, Discourse, Figure 354). The death drive responds (or has always already preemptively responded before order is imposed) by pushing the spool away: the death drive “is the ‘re-‘ of return or of re-petition, but in the sense of rejection, not of returning. It is not the play, but the un-play, the e-luding, the dis-placement” (Elle n'est pas le jeu, mais le dé-jeu, ce quis déjoue; le dé-placement.) (355; translation modified). It is the drive of energeic rhetoric toward figuration and away from literal order, even if only to bring it back into order.

The rhetorician uses metalepsis and then creates a handbook that safely compartmentalizes that metalepsis. The death drive pushes the spool away, infecting discourse with figuration; the subject pulls it back, now employing discourse alongside figure.

It is important to note here that the death drive is not directly equated with the figural. Instead, it is the motive for figuration: “Now we understand that the principle of figurality that is also the principle of unbinding (the un-play) [dé-jeu] is the death drive: ‘the absolute of anti-synthesis’” (355; translation modified).

This antisynthesis becomes even more important when we look at various rhetorical theories of oscillation.

From here you can move toward oscillation or coherence (or anywhere else you might like). My motivation for not synthesizing these moves is made more apparent where we discuss the differend.

Lifetime is a child at play, moving pieces in a game; kingship belongs to the child.

(Heraclitus, Fragment 52)

or non-locus: utopia

a„ën pa‹j ™sti pa…zwn, pesseÚwn:

paidÕj `h basilh…h.

(Heraclitus, Fragment 52)

Image of Building Stories, photo by author..

Image of page from Building Stories. Click to enlarge.

*In classical Latin, this pair lacked the distinction they have in English. Both transcendo and transgressio mean to “step over” (Lewis and Short). By the first century, transgressio has taken on technical meanings within rhetoric, with Quintillian using the term to refer to both hyperbaton and transition. Interestingly enough, Quintillian also uses transcendo to refer to transitions (4.1.79 and 7.1.21, each in the context of an improper transition). In fact, at the end of book four, chapter one, Quintillian uses each term within the span of three sentences, at first referring to transitions that should not be concealed (78, transgressio) and then to the act of transitioning too quickly (79, transcendo). Suffice to say, prior to the fourth century and Augustine and Ambrose’s uses of transgressio in a Christian context, transgressio appears to have no moral weight to it. Somewhere along the way they inverted to form our current pair.

“If one calls bricolage the necessity of borrowing one’s concepts from the text of a heritage which is more or less coherent or ruined, it must be said that every discourse is bricoleur. The engineer, whom Lévi-Strauss opposes to the bricoleur , should be the one to construct the totality of his language, syntax, and lexicon. In this sense the engineer is a myth.” (285)