x

Contents

Home

Home

Home

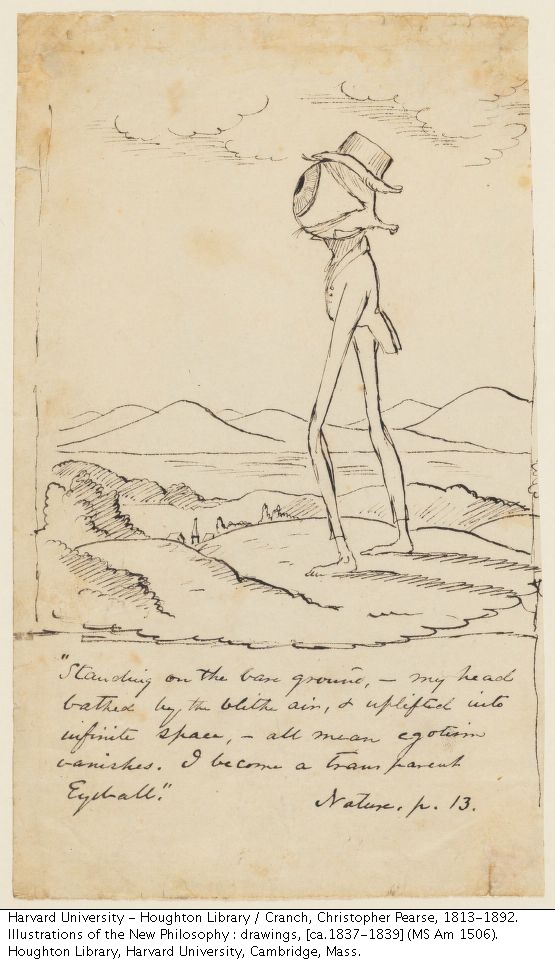

Standing on the bare ground,—my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite spaces,—all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Nature”

Toward a Transparent I

Fig. Cartoon of Emerson as a Transparent Eyeball from Thomas Cranch; “Cartoon of Emerson as a Transparent Eyeball”; Emerson’s Scholar: A Middlebury Tradition; Ed. Andrew Wentick et al.; midddigital.middlebury.edu/emerson, 2003; Web; 20 Mar. 2015. <http://midddigital.middlebury.edu/emerson/works/cartoon.htm>

Or to find a difference beyond opposition

discourse / figure

There are two aspects of the eye’s physiology across which we can build a structure for subsequent arguments.

First, there is peripheral vision. The distribution of rods and cones on the back of the eye makes peripheral vision more acute at seeing difference—black and white—and narrow vision more acute at seeing continuity—the range of color. While looking at stars, for example, the peripheral is far more able to distinguish these small balls of light against the dark sky, and every stargazer must learn to look near but not directly at.

Second, there is the parallax view. Three-dimensional space is a mental construction based upon two conflicting interpretations of the world—one from the left eye and one from the right. Even before getting into any kind of complex neuroscience, our perception of the world is hardly unmediated. It is a construction based on two witnesses, and those witnesses never agree.

Keeping these two figures in mind, we will proceed to discuss comics, through the two lenses of philosophy and art, but also as a center we must walk around.

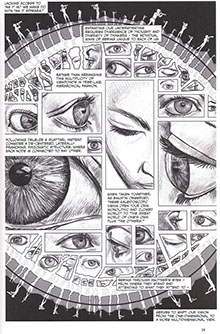

In his recent comic monograph Unflattening, Nick Sousanis employs the metaphor of parallax vision to discuss the relationship between image and text in comics (31). For Sousanis each mode acts as a different eye, offering us a unique perspective on the world. Comics combine these perspectives so that we might better approximate the world as it is. Unflattening was published a few weeks after I submitted my initial draft of this project to the publisher, and I’ve not been able to adequately integrate it into my argument. Nevertheless, I find it incredibly interesting that we each happened upon the same metaphor. I think it valuable to use this metaphor as a way of distinguishing our arguments.

In using the parallax metaphor, I am comparing the perspectives of two fields, art and philosophy. While these two fields are quite distinct from each other, it is also easy to see that they are on the same plane: the plane of academic discourse. Sounsanis, on the other hand, is connecting two modes: the visual and the verbal. As I argue in another nexus, the visual and verbal are radically different from each other, and yet they overlap in surprising ways. Sousanis seems to think of them as more or less distinct though ultimately similar ways of describing the world. In fact, following Langer, he describes both discursive and nondiscursive modes as a language (67). As I argue elsewhere, comics are not a language, and to see them as one can be impoverishing of both comics and language. Likewise, Sousanis sees the principle of imagination as a binding, whereas I argue (following Lyotard) that figuration follows the principle of the death drive, that of unbinding.

I stress these differences not to disparage Sousanis’s book, which is innovative, fascinating, and much more of a “pure” comic than my own. I don’t think I am right and he is wrong. Each of us is constructing arguments based on metaphors, and when the metaphors are similar, it is easy to read the arguments as identical. I want to make clear the ways we are differing so that my own arguments are not mapped directly onto his.

But for this nexus, we must return to our analysis of the eye through art and philosophy. One way to approach the eye is to follow its story’s teller, George Bataille:

The point of view I adopt is one that reveals the coordination of these potentialities. I do not seek to identify them with each other but I endeavor to find the point where they may converge beyond their mutual exclusiveness. (7)

Bataille’s figure of sex and death is at once parallax and peripheral, combinatory and superficial. Our task concerns concepts no less important: image and text, coupled with perception and action.

Images of pages 31 and 39 from Sousanis. Click to enlarge.

Detail from page 39 from Sousanis.

The discipline of optics takes the actual object and the virtual image as its starting points and shows in what circumstances that object becomes virtual, that image actual, and then how both object and image become either actual or virtual. (Deleuze, “Actual” n9)